1939 War and Exile Part 2

Note: During WW2 Hungary was on the side of the Axis Powers led by Germany. At the time of my father’s arrival there, Hungary was not yet involved in the war. Through its centuries long friendship with Poland, the Hungarians attitude to escaping Poles was ambiguous. Whilst officially co-operating with the Nazi authorities, the Hungarians help many Poles escape and my father was among them.

‘We arrived four days later at the small town of Kolomyja about 15 km from the Romanian border and were promptly arrested by the local Communist Committee for not having proper identification papers and for trying to escape from the USSR. We were told we were reactionaries and anti-communists and that we would be tried in the People’s Court for treason. However luck was with us – the Soviet authorities released us because the Russians were soon to celebrate the anniversary of the October revolution of 1917. We were granted an amnesty.

My friends and I then decided that it would be easier to cross to Hungary but this meant that we had to cross the German-Soviet demarcation line, which was the River San. Fortunately for us, the water level was quite low because of the very dry summer and we crossed over one night to the German side when it was quite dark. Immediately we turned south and headed for the mountains and the Hungarian border. It took us two days climbing and hiding from the German patrols. Three hours before we reached the border, on top of the Carpathian Mountain chain, it started to snow quite heavily. Although this made our progress more difficult and slower we thought because of it there would not be too many German patrols and therefore it would be safer. After many stoppages and crossings of streams, soaked to the skin, we reached the top of the mountain at about six o’clock in the morning and came upon the white stone marking the border with the Polish White Eagle on the north side and St. Stephens Crown of Hungary on the other. We tumbled down the mountain for about an hour and eventually came upon a path. We followed it and came upon a small cottage which happened to be a Hungarian border patrol guard house. There were three guards there and they asked if we were “Lengyel” which means Polish in Hungarian. They invited us inside, told us to dry our clothes, gave us blankets plenty of hot black coffee, brown bread and butter, and some hot wine as we dried near the fire. On this side of mountains there was not a sign of any snow and the day dawned bright and sunny.

It was now 18th November and it was my 18th birthday. The sergeant of the guards made a phone call about 3 o’clock in the afternoon; one of the guards took us to a small town about 15 km away and handed us to the Hungarian Military Authorities. From there we were sent to Budapest where I was sent to a hospital for treatment for my feet which I had injured badly crossing the mountains. I spent three weeks there after which they sent me to camp for Polish refugees near the little village of Tapsony, where I registered immediately to be sent to France in order to join the Polish Army in exile. I do not know to this day what happened to my two companions for I never saw them again. Like thousands of other Poles in exile, I spent my first Christmas on my own, separated from family, among strangers.

At the beginning of February 1940 I received a message from the Polish Consulate in Budapest, that I would be joining a group of Poles to travel to Yugoslavia (now particularly Croatia) at the beginning of March and that I should make arrangements to escape from my camp. As luck would have it I was sent to a military hospital in Budapest to be treated for a rash which had appeared all over my arms. This cleared up in three weeks and I was told I would be returning to the camp the following day. I did not wait as I already had a date for going to Yugoslavia. I packed my few things and walked out of the hospital that afternoon. I did not know Budapest but I reckoned that if I followed the River Danube going east I should arrive at Budapest city centre. I was right and soon found the Consulate where I was told that I would be leaving Budapest that evening for the Yugoslavian border. Two days later we crossed the River Drava into Yugoslavia, whose border guards welcomed is with open arms. They gave us bread and wine and after two days we arrived at the city of Zagreb, where we spent two days before moving on to Trieste. Through someone’s mistake, instead of travelling through Northern Italy to France, we arrived in Rome to the annoyance of the Polish Consulate. A few hours later we travelled north and arrived at Modane on the French-Italian border, then on to Northern France to Coetquiden in Brittany. At this stage, I must say that the Hungarians, Yugoslavians and Italians treated us with warmth and sympathy but the attitude of the French was practically hostile as if accusing us of being responsible for the fact that France was at war.

At Coetquiden, I was drafted into the officers school on a course that was six months initially. It was now the middle of April and that German Army invaded France in May and our battalion of cadets was sent eastwards to join in the fighting. Soon afterwards we were told to turn back. We were heading towards St. Nazaire when we heard the news from the war front. The French and British armies were in rapid retreat, driven back by the advancing Germans. The French government was in utter chaos and many of the cabinet did not want to fight on. The elite French divisions fought bravely, before escaping to England, but it was not enough as defeatism was rife among some elements away from the front line and some acts of treachery were perpetrated.

We hoped to board the British evacuation ships at St. Naziare but by the time we arrived, the fleet had sailed further south and eventually reached Bordeaux. We caught with the fleet at St. Jean de Luz a few kilometres from the Spanish border. From there we sailed for two days after boarding the ship. The ships were in convoy and we were afraid that we might be torpedoed by the German U-boats, but we were lucky and after a few days we arrived at Liverpool in England. From there we were transported to Biggar in Scotland where the new Polish Army, from small numbers was formed. I had escaped in one piece and I was ready to fight for my country from foreign soil.’

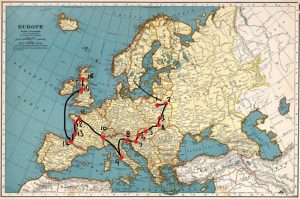

1. Brzesc nad Bugiem (then in Poland re-named Brest, now in Belarus)

2. Pinsk (then in Poland now in Belarus)

3. Lwow (then in Poland, re-named Lviv, now in Ukraine)

4. Kolomyja (then in Poland now in Ukraine)

5. Budapest

6. Tapsony ,

7. Zagreb (then in Yugoslavia, now Croatia)

8. Trieste

9. Rome

10. Modane

11. Coetquidan

12. St. Nazaire

13. Bordeaux

14. St. Jean de Luz

15. Liverpool

16. Biggar

And this was the beginning of my father’s exile. a journey of approximately 6,175 km or 3850 miles on foot and by whatever other mode of transport was available including stolen bicycles.

What of his father, mother and sister left behind? Their fate will be learned in the next two posts.

End